It seems fitting that WWF’s Living Planet Report 2024 arrived in my inbox the day Hurricane Milton slammed into my hometown.

I grew up on Little Sarasota Bay, with the Intracoastal Waterway and a view over to Siesta Key in the backyard.

When we moved into that waterfront house in the summer of 1981, jumping mullet slapped the surface of the bay constantly and pelicans were plentiful. Now you can spend the day in the backyard before you hear a mullet splash, pelicans are rarer, and an alligator was even spotted nearby—runoff makes the bay’s salt water brackish.

On September 26, 2024, the storm surge from Hurricane Helene flooded homes on our block for the first time; the water was several feet deep in living rooms.

Less than two weeks later, on Wednesday night, October 9, Milton, the second-most intense Atlantic hurricane ever recorded over the Gulf of Mexico, made landfall in a direct hit to Siesta Key.

Sunset at Siesta Beach in Siesta Key © Rebecca Self

We are at a Tipping Point

On the west coast of Florida, we’ve seen multiple hurricanes in a single year before, even in rapid succession, but the scale and intensity of these storms and their storm surges are unprecedented.

WWF’s report makes clear something Floridians are seeing firsthand: we are at a tipping point.

What is a tipping point? The term has been applied to a wide variety of processes in which, beyond a certain point, the rate of the process increases dramatically. From human behavioral sciences like economics and sociology to epidemiology, ecology and physics, the fundamental notion remains the same. In colloquial terms, if we were being pessimistic, we might call it the point of no return.

WWF’s Living Planet Report 2024 authors describe tipping points as:

“When cumulative impacts reach a threshold, the change becomes self-perpetuating, resulting in substantial, often abrupt and potentially irreversible change – a tipping point.

The Living Planet Report details numerous case studies in which ecological degradation combined with climate change increases the likelihood of reaching local and regional tipping points:

- North America: fire suppression, drought and pest invasion

- Great Barrier Reef: overfishing, pollution and warming waters

- India: wetland loss, drought and flooding

- Tipping points with global impact: drought in Amazon Rainforest, Greenland’s melting ice

Tipping points, whether local, regional or planetary, can initially be gradual, but then sudden and irreversible. Ecosystems may not instantaneously change from one state to another, but beyond a certain point of stress, change becomes unavoidable and rapid.

The Power of Positive Tipping Points

There are also positive tipping points. For example, former U.S. Vice President Al Gore has long used the term tipping point in a different way, fighting climate inaction and despair with the power of positive tipping points.

In a recent interview, he shared his belief, and rationale, that we are at a political tipping point:

- The power of fossil fuel companies to determine legislative outcomes is diminishing. Surging oil and gas costs spur governments to decarbonize faster, and fossil fuels are losing the electricity generation marketplace.

- Last year, worldwide, 90% of the new (generating capacity) was renewable. (Fossil fuel companies are in) the process of losing their second-largest market, transportation. The job market reflects this shift, with the clean economy generating three times as many jobs.

Momentum toward positive tipping points is undeniably growing; WWF’s report shows it’s just not fast enough.

Takeaway #1: Double down on support

In the face of global tipping points, WWF’s Living Planet Report asserts it is urgent to recognize the interconnectedness of nature, climate and human well-being. Tackling climate, biodiversity and development goals together simultaneously opens up opportunities to conserve and restore nature, mitigate and adapt to climate change, and improve human well-being.

My first takeaway from the report is to redouble my own efforts to support businesses, non-governmental and political organizations and individuals actively addressing ecological tipping points—to build toward positive, regenerative tipping points.

What is WWF’s Living Planet Report?

WWF’s Living Planet Report (LPR) is a comprehensive study of trends in global biodiversity and the health of the planet. Now in its 15th edition, the report provides a science-led overview of the state of the natural world and includes the Living Planet Index (LPI), which tracks how species populations are faring around the world.

This year’s Living Planet report reveals a catastrophic 73% decline in the average size of monitored wildlife populations over just 50 years from 1970 to 2020.

I was born in Tampa, Florida, in 1970. The report indicates that in my lifetime, based on almost 35,000 population trends and 5,495 species of amphibians, birds, fish, mammals and reptiles:

- Freshwater populations have suffered the heaviest declines, falling by 85%,

- terrestrial (69%) and

- marine populations (56%).

At a regional level, the fastest declines have been seen in:

- Latin America and the Caribbean—a staggering 95% decline

- Africa (76%) and

- Asia and the Pacific (60%).

Declines have been less dramatic in Europe and Central Asia (35%) and North America (39%) because large-scale impacts on nature were already apparent before 1970; some populations have stabilized or increased thanks to conservation efforts and species reintroductions.

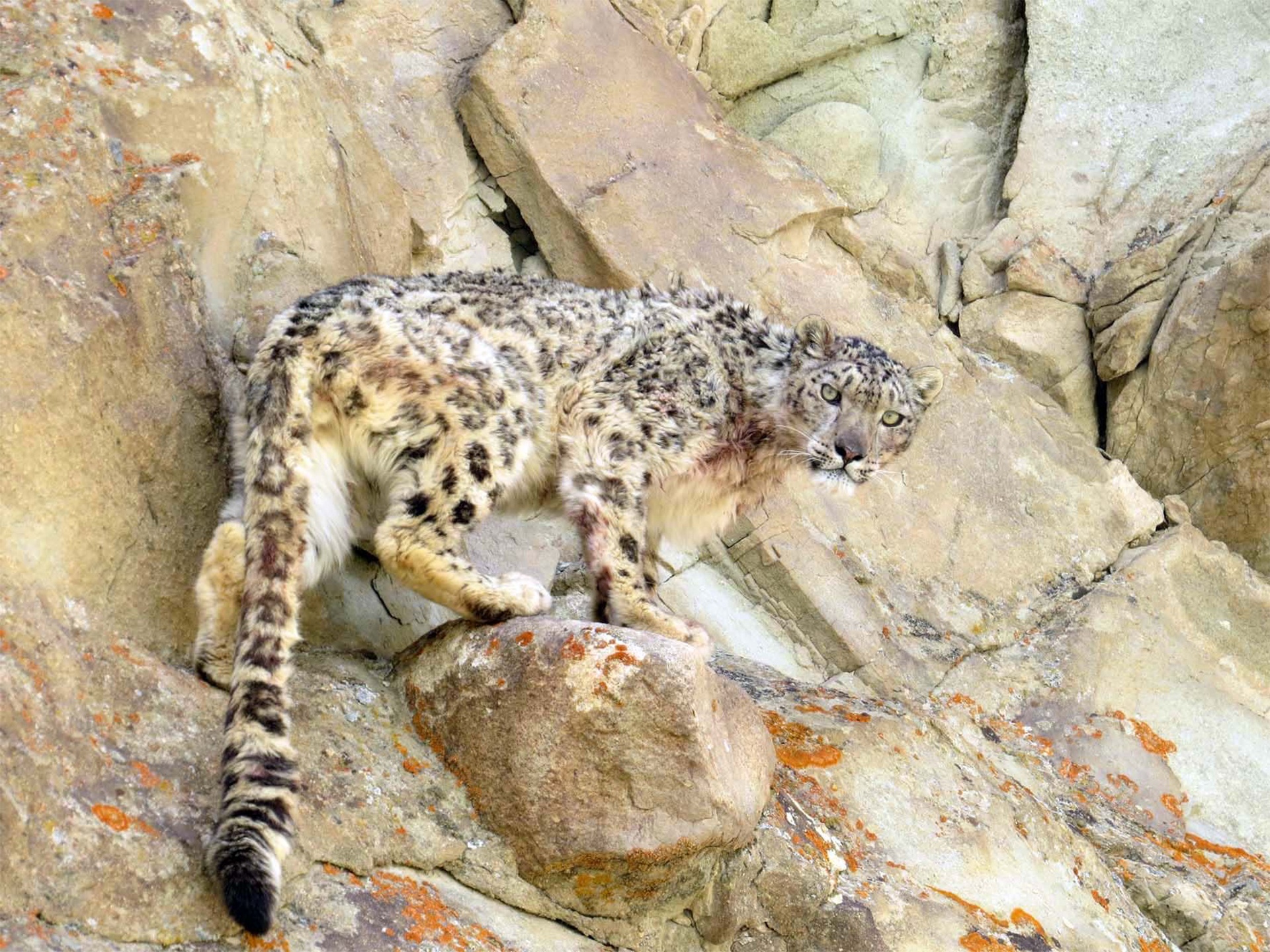

Wolverine, Russia.

What is the Living Planet Index?

The LPI monitors changes in the size of species populations over time, which is an early warning indicator of extinction risk and helps us understand ecosystem health.

When a population falls below a certain level, a species may not be able to perform its usual role within the ecosystem—whether that’s seed dispersal, pollination, grazing, nutrient cycling or other processes that keep ecosystems functioning.

Stable populations provide resilience against disturbances like disease and extreme weather events; a decline in populations, as shown in the global LPI, decreases resilience and threatens the functioning of the ecosystem.

Kirsten Schuijt, Director General, WWF International, shared:

“The linked crises of nature loss and climate change are pushing wildlife and ecosystems beyond their limits, with dangerous global tipping points threatening to damage Earth’s life-support systems and destabilize societies.

Although the situation is desperate, we are not yet past the point of no return. The decisions made and action taken over the next five years will be crucial for the future of life on Earth. The power—and opportunity—are in our hands to change the trajectory. We can restore our living planet if we act now.”

Wildlife Russia. Tiger in the water pool in the forest habitat. Siberian tiger cat in the lake.

Takeaway #2: Focus on Solutions

There is good news, too: despite the alarming overall decline in species populations, many populations have stabilized or increased as a result of conservation efforts. Protected and conserved areas have slowed the extinction rate for mammals, birds and amphibians by an estimated 20–29%. Recent analysis showed that conservation actions have had a net positive effect.

Isolated successes, species-based approaches, and merely slowing nature’s decline are not enough. We need to do more, faster, and in a more coordinated, regenerative way.

It’s a message Al Gore has been sharing for decades, and his stress is on solutions, too. He says:

“A lot of people go straight from denial to despair without pausing, intermediate, to solving the problem. And so that’s definitely an issue and I have been emphasizing justifiable optimism for quite a long time. And it’s not an artifice.

…We are gaining momentum in an impressive way and we have the basis for success. …We’re in the midst of a major sustainability revolution that has the magnitude of the Industrial Revolution coupled with the speed of the digital revolution. …It is still undeniably true that the crisis is still getting worse faster than we have yet begun to deploy these available solutions. Now we are gaining momentum, and I’m certain that we will soon be gaining on the crisis itself.”

In his climate presentations and trainings, Gore ends with a call to take hopeful action, emphasizing facts like:

- If and when we reach true net zero, the temperatures on Earth will stop going up with a lag time of as little as three to five years.

- If we stay at true net zero, half of the human-caused CO2 will fall out of the atmosphere in as little as 25 to 30 years.

My second takeaway from the Living Planet Report is really a reminder: all the solutions we need already exist. We already have the frameworks, technologies and nature-based solutions needed. This is a matter of will and collective action.

WWF’s Living Planet Report provides a framework for solutions, pointing to 4 urgent transformations to focus upon.

Sloth in nature habitat. Beautiful Hoffman’s Two-toed Sloth, Choloepus hoffmanni, climbing on the tree in dark green forest vegetation. Cute animal in the habitat, Costa Rica. Wildlife in jungle.

WWF’s Living Planet Report: The 4 Transformations

To maintain a living planet where people and nature thrive, we need collective action that meets the scale of the challenge, including more coordinated, effective conservation efforts while addressing drivers of nature loss. It will require nothing less than a transformation of our food, energy and finance systems.

Transforming Conservation

Protected areas currently cover 16% of the planet’s lands and 8% of its oceans. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) calls for 30% of lands, waters and sea to be protected by 2030, and to restore 30% of degraded areas by 2030.

Countries need to:

- extend, enhance, connect and properly fund systems of protected areas in a fair and inclusive way.

- Effective conservation outside of protected areas is also essential.

Wildlife ranger protecting Uganda and Rwanda’s great apes © Richard de Gouveia

Transforming Food Systems

Food production is one of the main drivers of nature’s decline: it uses 40% of all habitable land, is the leading cause of habitat loss, accounts for 70% of water use and is responsible for over a quarter of greenhouse gas emissions.

Coordinated action is needed to:

- scale up nature-positive production to provide enough food for everyone while also allowing nature to flourish;

- reduce food loss and waste;

- increase financial support and foster good governance including by redirecting environmentally harmful subsidies.

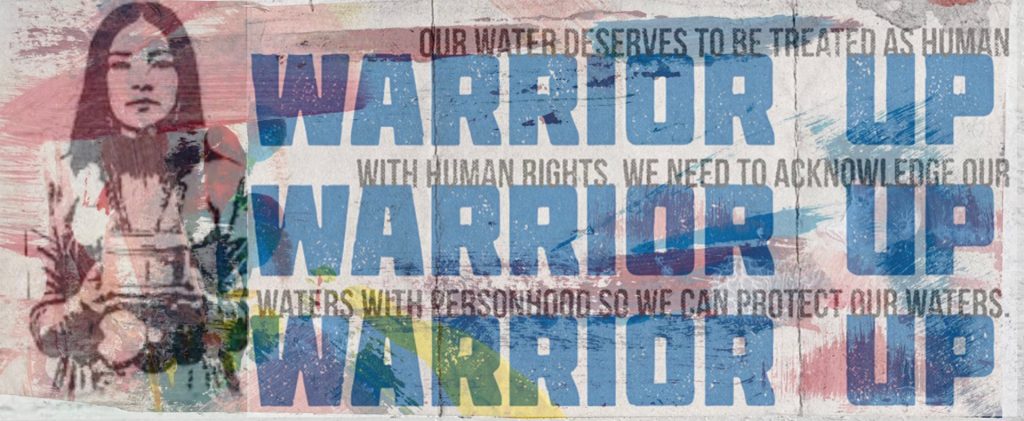

Indigenous women harvesting tea, Sri Lanka.

The way we produce and consume energy is the principal driver of climate change. We must

rapidly transition away from fossil fuels to cut greenhouse emissions in half by 2030. In the last

decade, global renewable energy capacity has roughly doubled; costs for wind, solar and

batteries have fallen by up to 85%.

Over the next five years, we need to:

- triple renewable energy,

- double energy efficiency,

- modernize energy grids.

Nat Hab Electric Safari Vehicle © Justin Sullivan

Redirecting finance toward business models and activities that contribute to the global goals on nature, climate and sustainable development is essential. Globally, over half of GDP (55%)—or an estimated US $58 trillion—is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services. Our current economic system values nature at close to zero. In fact, private finance, tax incentives and subsidies that exacerbate climate change, biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation are estimated at almost $7 trillion US dollars per year.

Financing green involves mobilizing finance for conservation and climate impact at scale, while greening finance entails aligning financial systems to deliver nature, climate and sustainable development goals. We need both.

Living Planet Report Takeaway #3: Share the Story

The Report states that what happens in the next five years will determine the future of life on Earth. What can we each do?

I heard an idea at the Mountainfilm Festival earlier this year that has stuck with me:

As explorers and travelers, our returns are essential. How we share our adventures and expeditions determines how exploration makes a difference and how it translates into action toward positive tipping points.

I am a researcher, writer, leadership advisor and professor; that’s how I make a difference. Photographers document the environment and practice visual advocacy when they share their photos and the stories behind them.

How will you contribute toward transformation and positive tipping points? Are groups and organizations you are a part of driving transformation?

Sunda bearded pigs, Borneo, Malaysia.

How We’re Transforming Travel

At Nat Hab, we’re working to transform travel so it contributes to the conservation and regeneration of the local communities and wild places we visit. Our mission is conservation through exploration: protecting our planet by inspiring travelers, supporting local communities and boldly influencing the entire travel industry.

Since 2007, Natural Habitat Adventures has been the world’s first 100% carbon-neutral travel company. We embarked on that ambitious project in partnership with Sustainable Travel International, reducing and offsetting the carbon emissions that result from all office- and trip-related activities.

In 2018, we began partnering with South Pole, a sustainability consultancy that works with businesses and governments to reduce carbon impacts by offsetting greenhouse gas emissions via third-party verified projects around the world. In 2019, we offset all our travelers’ flights to and from our global adventure destinations, increasing the total amount of our carbon offset by 300-400%.

Nat Hab & WWF “Discovering Our Planet Together.” Photographed by Nat Hab Expedition Leader & Sustainability Director © Court Whelan

Nat Hab’s efforts are currently focused in these areas:

Conservation travel makes natural habitats even more valuable and appreciated by bringing positive attention and economic resources into local communities. From Madagascar to Namibia, conservation travel has inspired individuals and whole communities to protect wild places and the life that thrives there. Our hope is that after travelers experience the beauty and silence of the wilderness, they become ambassadors for conservation in their own communities.

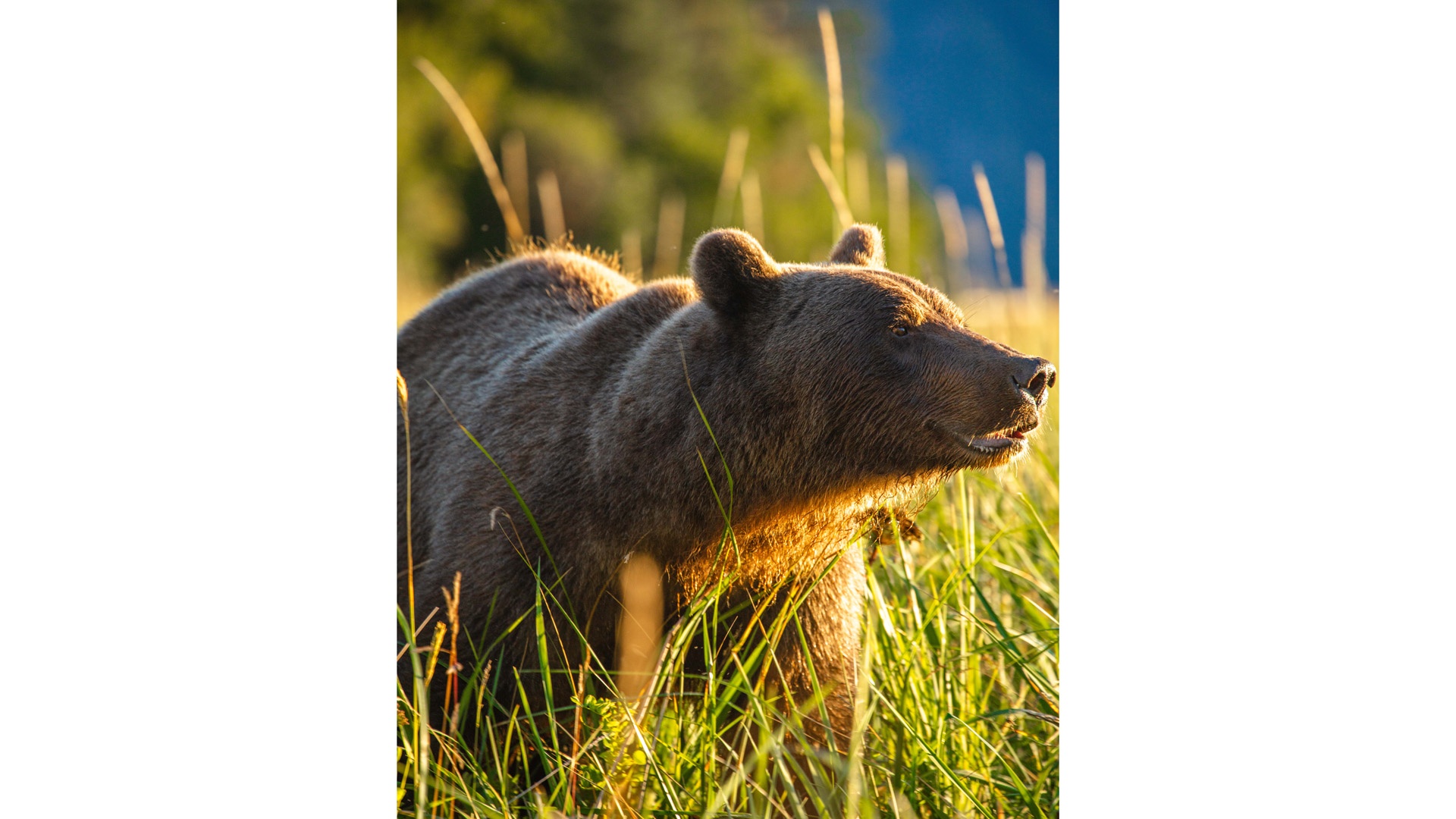

Coastal brown bear in Lake Clark National Park. Photographed at Nat Hab’s Alaska Bear Camp by Expedition Leader © Rylee Jensen

The post WWF’s Living Planet Report: Biodiversity, the Climate Crisis & What’s Next first appeared on Good Nature Travel Blog.